Recently, I had the rare opportunity to spend time inside the U.S. Department of the Treasury, where I was invited to meet with the building’s curator and was given a private tour. I was there initially to look at a potential project, but as often happens when you’re surrounded by craftsmanship, the building itself quickly became the focus.

We entered through the public side of the building, and as we walked, the curator and I talked about the history of the space—how it has evolved, how it has been maintained, and how much care goes into understanding what still exists beneath decades of change.

At first glance, many of the corridors are painted a very straightforward white. Not a bright white—more of a soft, institutional white. Clean, orderly, restrained. Nothing flashy. Just functional.

But as I walked beneath the ceilings, my eye kept drifting upward.

Even in these quiet corridors, the plasterwork above told a different story. Ornate moldings, beautifully proportioned details, and a level of craftsmanship you don’t see much anymore. And then I noticed a plaque on the wall.

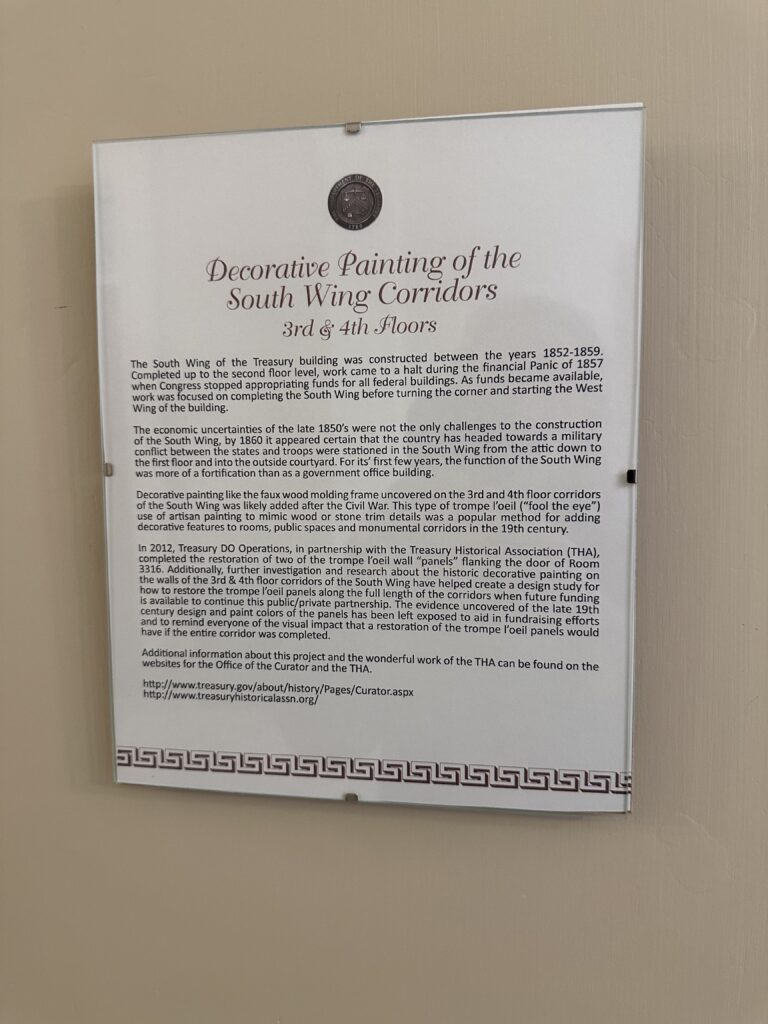

It explained that these corridors were once richly decorated using trompe-l’œil—a painting technique designed to create the illusion of architectural depth. Painted panels, shadows, and detailing were used to make the corridors feel taller, longer, and more expansive than they actually were. It wasn’t decoration for decoration’s sake; it was visual architecture, thoughtfully designed to shape how people experienced the space.

Standing there, it wasn’t hard to imagine how dramatic those corridors must have felt when they were fully realized.

As we continued walking—white corridor after white corridor—I was now seeing them differently. Knowing what once existed beneath the paint changes how you look at everything.

Then, at the end of one corridor, I made a left turn—and there it was.

A gilded eagle.

It sat there almost quietly, catching the light in a way that immediately set it apart. The curator explained that conservators had been doing surface analysis—carefully examining layers of paint and finishes to understand what was original and what had come later. Through that research, they discovered that this eagle, and much more throughout the building, had once been fully gilded. Over time, it had been painted over, like so many historic surfaces tend to be.

Records are somewhat fuzzy, but the research suggests that much of the gilding was added or enhanced in the period following the Civil War, when the building underwent changes reflecting both growth and renewed symbolism.

Knowing that, I walked on with a different awareness. Hints of trompe-l’œil. Hints of gold. Clues everywhere.

Then I made another turn.

Just a few steps later, I entered the original grand entry.

And I stopped.

The difference was immediate and overwhelming—in the best way. Soft pink walls, extensive gilding, and an extraordinary balance of color and ornamentation. Gold traced the plasterwork, not overpowering it, but enhancing it—highlighting the craftsmanship underneath in a way that white paint never could.

What struck me most was the warmth. You might expect a space with this much gold to feel cold or overly formal, but it didn’t. It felt calm. Inviting. Grounded. The colors worked together so naturally that you just wanted to stand there and look—really look.

And then you notice something else.

From that spot, you can actually see how abruptly it ends.

The grand entry, rich with color and gold, stops almost mid-thought. Straight ahead, the view shifts back into the white-painted corridors beyond. No gradual transition. No easing out of the ornament. Just a clear, visible line between what once was and what came later.

Seeing both at once makes everything click.

It’s one thing to read about historic finishes being lost over time. It’s another thing entirely to see that contrast with your own eyes.

As someone who works with traditional materials, I couldn’t help but think about what went into creating these surfaces in the first place.

Gilding isn’t just about applying gold—it’s about patience and precision. Gold leaf is made by hammering gold into sheets so thin they can move with the slightest breath of air. The sheets are so delicate that touching them with your fingers can cause them to tear instantly, the natural oils breaking them apart. Traditionally, gilders used specialized brushes—often made from squirrel hair—relying on static electricity to lift and place the gold gently onto prepared surfaces.

And those surfaces mattered. In this building, the gilding was applied over plaster—meticulously prepared, sealed, and coated to receive the gold. Every step required steady hands, calm focus, and time. The same goes for the plaster ornamentation itself. The skill, patience, and confidence it takes to create work like this—let alone gild it—are hard to fully appreciate unless you’ve spent time doing it.

Even the painted walls deserve attention. They’re flawless. No brush marks. No roller lines. The light dances evenly across them, applied at just the right angle, with just the right consistency. It’s the kind of craftsmanship that disappears when done well—but once you notice it, you can’t unsee it.

The Treasury Building itself was constructed beginning in the 1830s, with significant expansions through the mid-19th century. It was commissioned by the federal government and designed by multiple architects over time, including Robert Mills and later Thomas U. Walter—names closely associated with America’s most important civic architecture. What you see today is the result of decades of design decisions layered one over another, each reflecting the values and priorities of its moment.

Standing there, surrounded by gold, plaster, and history, I felt a deep appreciation—not just for how beautiful the space is, but for how carefully it has been studied, preserved, and respected.

This visit felt like the beginning of something rather than a conclusion. There is so much more of the building to explore, and I’ve been given permission to share select images and details along the way. Over the coming weeks, I’ll be posting more from this visit—more discoveries, more craftsmanship, and more quiet moments where history reveals itself if you’re willing to slow down and look.

Sometimes, the most interesting stories aren’t the loud ones.

They’re the ones hidden just beneath the surface.